Father’s Day Reflections — A Man Who Simply Wanted To Be Considered Equal

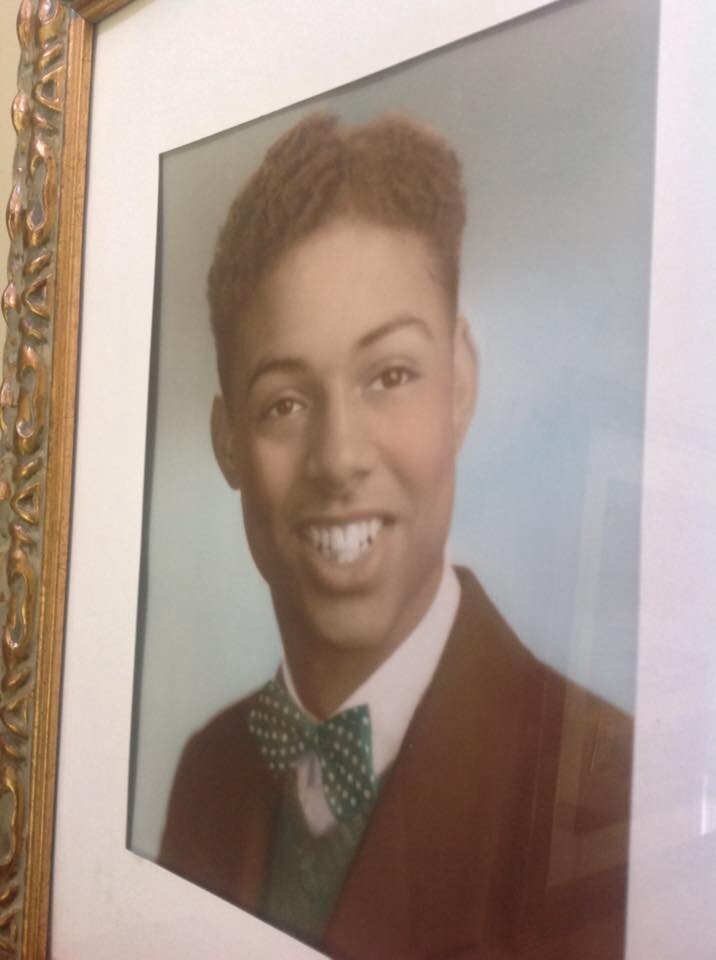

My dad, William Earl Williams, was born on August 6, 1929 in New Bern, N.C. Shortly after his birth, his father was killed in a tragic football accident. He and his mother, Estelle, headed to NYC looking for a better life. His mother, a mix of African and Native American blood, was a beautiful, strong-willed and proud woman. She worked as a domestic and later in a hospital to support her and my dad. They moved around often from apartment to apartment from Brooklyn to Harlem to Queens.

Life was not easy for them. What many do not realize is how difficult it was for black women who were domestics (live in maids/nannies/servants) to survive. She was a young mother in her early 20s who had to literally leave her young child home alone for days and days while she lived with a white family, cleaning their home and raising their children on the north shore of Long Island. My dad, not yet the age of ten, had to grow up quickly, learn to take care of himself with loose supervision from neighbors and shop keepers in the neighborhood who kept an eye on him for my grandmother. She was so happy when she finally landed a job in a hospital as a nurses aid, a job not given to many black women in those days. This enabled her to be home with my father more regularly. Imagine having to live this way, with employers who didn’t care what sacrifices you had to make to work for them, including not being present with your child.

When my father was in his early teens, about 13 or 14 years old, while living in Harlem, he worked at a local store, owned by an Irish man named Mr. Welch. One day, on his way to work, he was jumped by a bunch of Irish boys who were known gang members. They yelled, “get the n — — — -r!” After a lengthy chase that ended up near the river, they caught my dad, beat him up, stripped him of his clothes and threw him in the river. Not able to swim well, he doggy paddled and was carried by the strong river downtown. He was lucky enough to make it to shore and was spotted by a cop. This big, white, Irish cop saw my dad shivering and gathered some newspapers, gave them to my father and told him to cover himself. He then asked where he lived. My father said Harlem. The cop told him to go home. He never asked him what happened, or why are you naked? Just said go home. Didn’t call for a squad car to come and drive him home. Just said to go home. Imagine if he saw a young white boy in this condition. Would he have just said to go home?

My dad served in the Army during the Korean War. He was a Master Sergeant. His first wife, not my mother, went to visit him while he was stationed at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. She was very fair skinned and looked white. They were arrested and detained by local police because it was illegal for whites and blacks to be with another romantically, let alone married. Mind you, he was in a US. Army uniform with stripes on his shoulder, but none of that mattered. They were not released until they could provide papers proving she was black, not white.

While on a special assignment where my father was leading a detail of three black soldiers and one white soldier as they were transporting German prisoners of war from WWII from Fort Campbell to Washington, D.C. another insidious incident took place. They stopped along the way to change locomotives on the train they were on. So, my father decided they would use the opportunity to get a meal before continuing on their way to DC. The restaurant wouldn’t serve the black soldiers including my father who was in charge of the detail. But, they served the white soldier and the 12 white, German prisoners. How do you like that?

My grandmother and father worked hard , saved their money and had high hopes of moving out of the public housing community they lived at in Queens, NY. Hoping to purchase a home in Levittown, NY, a new community in the suburbs of Long Island available to Veterans through the G.I. Bill, they went to the sales office to inquire about a home and to see the model home. Needless to say, after hours of humiliation and being ignored, they were told, “These homes are not available for your kind.” This crushed my grandmother’s hopes and spirit. Yet, just another set back and lesson for my father to learn and endure.

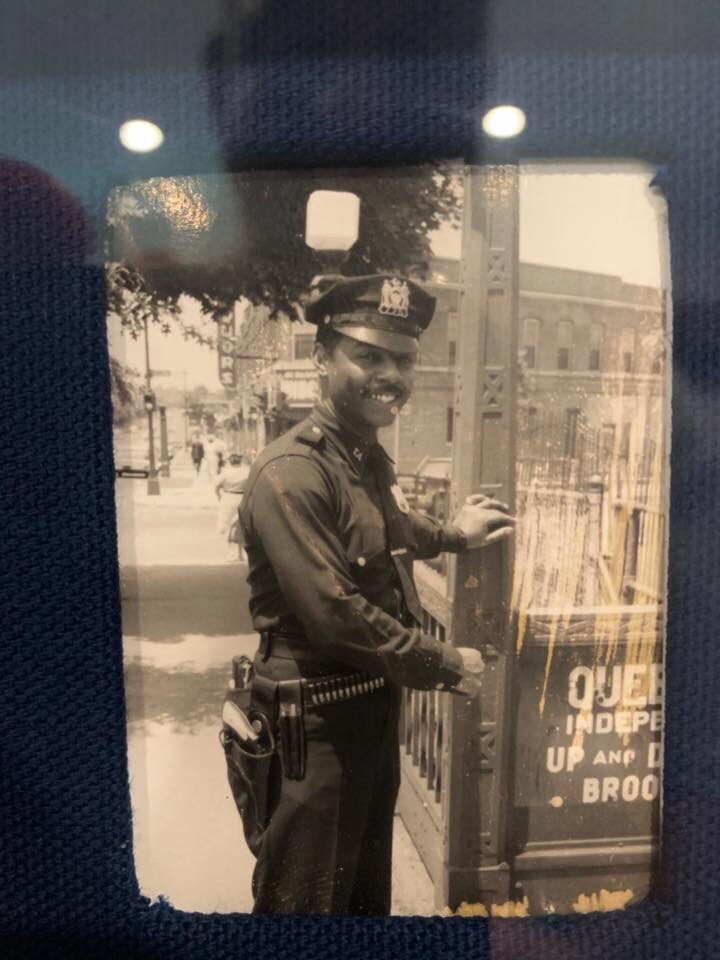

After fighting and clawing to get on the New York City Transit Police Department, dad finally thought he made it. He had been selected into the recruit class with one of the largest cohorts of black officers. As a member of those brave and proud black men that included the father of Kareem Abdul Jabaar, my dad finally achieved a job that gave him some status and pride. You see he was never afraid of hard work. He worked in the print office of the United Nations, he worked printing covers for Life Magazine and he got a job in the New York Department of Sanitation, a job long controlled by Italian Americans. But, finally, he had earned a spot on the police department.

One day while on patrol, he sees a little white boy, probably about 5 or 6 years old. My dad is smiling at him while the mother is looking for something in her purse. The little boy exclaims while pointing at my dad with many others around and in earshot. “Mommy, look at the n- - - - r cop”. My dad in that moment realized no matter the uniform he is wearing, he is just a n- - - - r.

He endured so much cruelty, injustice, and racism while on that job. White officers tried to set him up so he would get fired by paying a prostitute to come on to him while he was patrolling his subway station. He was smarter than that, didn’t fall for it, and got her to admit she was paid to set him up. But, supervisors on the job did nothing about it. He was promoted as a provisional sergeant, a role he performed exceedingly well. But, after fulfilling the role well, receiving commendations for doing so, it was taken away from him and he was never promoted to that rank, even though he showed he was qualified. I could go on and on, but will hold these stories for another day.

Sometime in the early 1960s my mom, Dolores and my dad went to the newly built, luxury apartment complex on Long Island, called North Shore Towers to see about purchasing an apartment for our family. Simply said, they were given the run around and not shown any apartments. You see, like so many places on L.I. and across the country, blacks were not to be sold to. To this day, when I pass those towers on the Grand Central Parkway, it infuriates me!

Bear with me, as I share just a few more reflections. My parents sent me and my sisters, Tiffany and Sandra, to a private school, located in an all white neighborhood called Garden City, NY. I recall two occasions where I naively asked my dad questions that caused him great embarrassment and shame. On one occasion I asked him why we didn’t live in Garden City, closer to school. He had to explain to me that black people were not welcome to live there. The other was while we were driving to school and passing the Cherry Valley Golf Club, I asked him why he didn’t play golf. He responded, “Scotty, golf is not a game for black men. We are not allowed to join their clubs or to play their game, but they will allow us to serve them food and carry their golf clubs and shine their shoes!”

When I was about 10 years old, my dad and I were doing some yard work. It was Memorial Day or Fourth of July. I noticed many of our neighbors, all white families had flags hanging in front of their homes. I asked my dad why we didn’t fly a flag at our home. He looked at me with a very serious look and said, “Son, as long as we are not considered human beings and recognized as equals in this country and by this country we will never fly a flag at this home!” That was the first time I heard the story about him being denied a meal while transporting German prisoners of war.

I held on to that message my entire life. My dad, despite the many injustices he experienced, the racism he endured, never let those nasty, cruel experiences color his outlook on life or how he treated white people. He taught his kids to love and respect our country, to treat people well regardless of race, religion or creed, and to not judge. He searched for the good in humanity, even after living a life being kicked in the teeth by racism and bigotry. He died a true Patriot. He loved his family, his country and his God!

He didn’t live long enough to see this country elect a black man as its President. The day after President Obama was sworn into office, I purchased a flag, said a prayer for my father and proudly hung that flag from my home.

Dad, thank you for enduring all the pain and hardships, fighting the good fight and working so hard to give your children a better life than you and mommy lived through. Things have gotten better in some ways, but yet remain the same in so many ways. We will keep fighting for equality and justice because I know that is what you taught us to do and what you expect from us. You would be so proud to see your grandson, Will who is named after you, standing up so bravely and boldly for justice too!

I love you, I miss you, especially today…Happy Father’s Day!

I share these stories, not to make people feel guilty, but to help people realize this is part of our history through one man’s life experience. Multiply these stories by all of the black men and women throughout the history of our country and you realize how real and tragic our history is. These things happened and continue to happen. It is up to all of us who are good and who care to make real and lasting change.

I must thank Dr. Richard Skolnik for helping my dad to write his life’s story in his biography, “I Am The American” many of these stories come from his book and a few shared orally with me and my sisters.